The world’s best cuisines all use eggplant.

See for yourself.

Wise Living Magazine

RecipeTinEats

Who Does the Dishes

The more a country uses eggplant, the better its food. Think of grilled nasu dengaku in Japan, baba ganoush in the Middle East, Italy’s lasagna melanzane. Conversely, cultures without an abundance of aubergine find themselves in a dire situation, forced to rely on inferior vegetables.

The Three Commandments

Treat the eggplant as you would want to be treated. Tenderly caressed, oiled, lightly seasoned and cooked with care. Sounds good, right?

Add oil

Or, as the Chinese would say, jiāyóu (good luck). Eggplant is a vegetable – well, technically a berry – that is fundamentally soft, unctuous, luxurious. It needs to be treated with appropriate lashings of oil. That’s not to say it need be unhealthy, just pick the right method. Don’t try and grill eggplant slices without enough oil. Down that path leads misery. Roasting a whole eggplant, on the other hand, keeps the moisture inside and lets you season as you like with oil and salt at the end.

Gently, gently

When cooked properly, eggplants become a special thing. Delicate and tender, you must take great care not to have them disintegrate. American globe eggplants tend to be more hardy than, for example, Thai, Japanese or Chinese eggplant. Treat them gently, or you’ll find eggplant-flavoured paste throughout your dish. Of course, there are also a great many dips and spreads – baba ganoush being the most legendary – which make use of this softness, adding oil, salt and spices to create a gift from the gods.

A pre-cook salting?

Salting eggplant thirty to sixty minutes before cooking is supposed to draw out the bitterness. While eggplant seeds do contain a bitter compound related to tobacco (also of the nightshade family), this flavour has a) largely now been selectively bred out and b) is mostly limited to the large, black eggplant common in America (bigger, older eggplant = more seeds). That’s not to say salting has no value: similar to brining meat, you’re drawing out moisture and concentrating the eggplant flavours. You’re also making it harder for oil to penetrate, so it’s particularly useful for deep-frying. Just make sure you thoroughly dry your eggplant before dunking in boiling oil. At the end of the day, you don’t need to pre-salt your eggplant. Seasoning during cooking, however, is non-negotiable.

Eggplant//

Aubergine//

Brinjal//

Melanzana//

Al-bāḏinjān//

Qiézi//

Eggplant has been around longer than written language, and its many names around the world reflect this. Its names also reflect its origin – uncertain, but likely Northern Africa or Southern India, where it grows wild.

The first known written reference to eggplant is in a 59 BC Chinese slave contract1. The contract is a tongue-in-cheek listing of a recalcitrant slave woman’s duties, listing an impossible number of tasks to be completed each day, even including simpler tasks to be completed in old age. One of these tasks is: “In the second month of the year, the Spring Equinox … separate and transplant seedlings of eggplant and scallion”.

Eggplants arrived in Europe by way of the Moors in Spain. These were small, white, egg-shaped lobes of fruit, hence the English name. At some point, they were bred with purple skin, likely first as a novelty. 2

A thirteenth-century Italian text calls eggplants the ‘mad apple’, mela insana, becoming melanzane – perhaps reflecting changing cultivars. 3 But in the same way that an ancient banana or ear of corn looks and tastes very different to a modern, selectively-bred one, medieval eggplants would have been quite bitter, hence why older recipes recommend soaking or salting in advance.

By the 18th century, eggplants were being grown in England as a novelty and source of comfort to migrant Italians and Spaniards. They wouldn’t have reached the full ripeness of Mediterranean eggplants without hothouses, which weren’t widespread in England at the time. A couple of 18th century sources detail how eggplants were eaten at the time around Europe. 4

Today, eggplant is the sixth-most farmed crop globally, feeding and bringing joy to billions. Truly, a crop that has evolved with humanity, feeding us from the cradles of civilisation to the megacities of tomorrow.

How it started 🌱

Eggplant curiosity.

How it’s going 🍆

Eggplant insanity.

The story of eggplant is, in many ways, the story of civilization. Some of the regions in which it’s used today are the birthplaces of humanity: the fertile valleys of Mesopotamia, the varied biomes of Turkey, the harsh deserts and lush farmland of Egypt.

The Eggplant Belt represents a region of concentrated eggplant production and consumption. Note the favourable growing conditions and excellent food throughout.

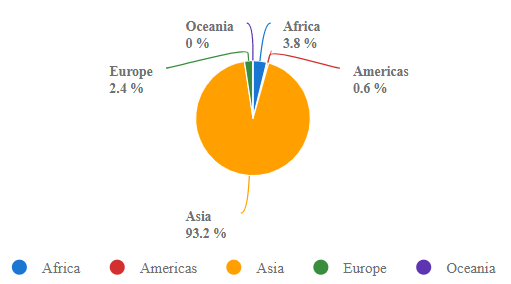

In constructing an actual index, there are a few things to consider. First, there isn’t much reliable consumption data, so we have to rely on production figures. Then, consider the export markets. Is eggplant even exported? Spain is the world’s largest eggplant exporter by value (China’s exports make up only 4% of the global total). At US$20m export value and US$16.8bn total domestic production, China exports just 0.001% of its total eggplant production. So given China grows 78% of the world’s eggplants, and its exports of that are effectively a rounding error, almost all eggplant grown in China is consumed there. Eggplant has a fairly short shelf life and while it is a relatively high-value crop (earning approximately $17,500 per acre in the US) the high labour costs and low density mean it’s mostly grown in greenhouses for domestic markets. By density, it’s as simple as one kilogram of eggplant taking up far more space than one kilogram of asparagus, avocado or pineapple. Is it any wonder that the most-exported crops globally are cheap, energy-dense staples with multiple uses (and often supported by government subsidies) such as corn, rice, wheat and palm oil?

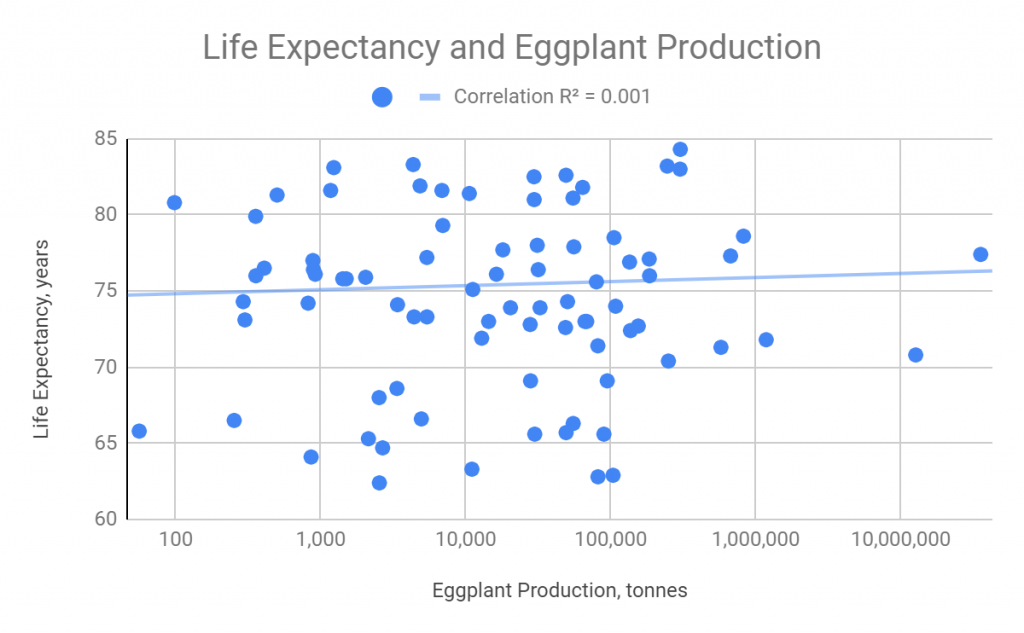

So, running the numbers, just 1% of global eggplant production is exported. 5 We can then use production figures as a proxy for consumption. The tricky part is finding an objective measure of cuisine quality. How about looking for a relationship between life expectancy and eggplant production? Not much there.

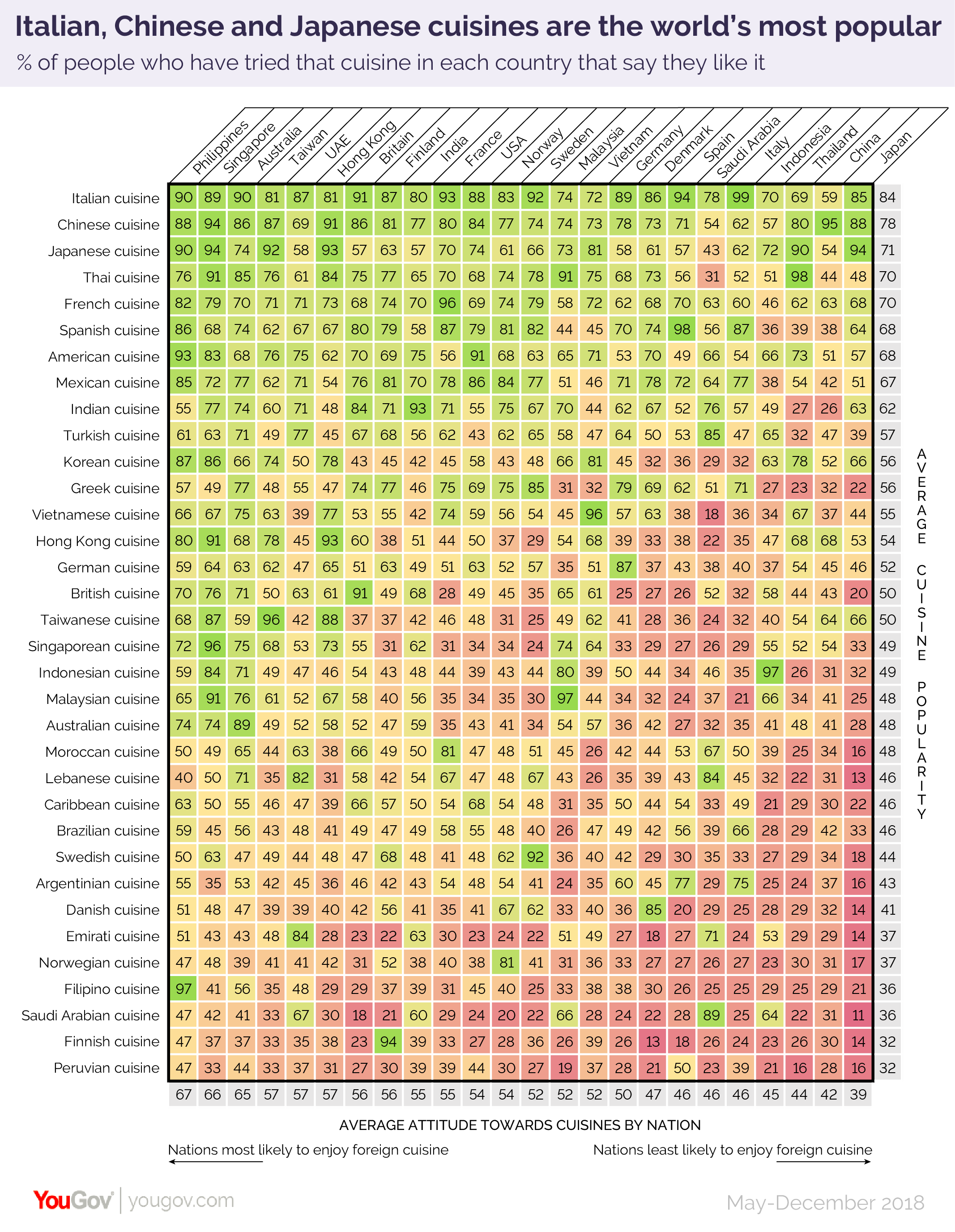

But a 2019 YouGov poll surveyed people from 24 countries to find out which cuisines were the most popular. The results are interesting – for example, it looks like countries with more popular cuisines themselves like fewer other types of food. That makes sense: if you’re Italian, Chinese or Japanese, it’s likely the majority of other cuisines you encounter will be inferior to your own – and certainly by your own judgment.

But more useful is that we can use this data to work out if there’s any link between a country’s cuisine’s popularity and their eggplant production (and, as established earlier, their eggplant consumption). Here, we have more success. There is a weak relationship between the popularity of any given cuisine and the extent to which they produce eggplant.

The strength of this relationship may even be slightly under-represented, as I couldn’t find eggplant production data for several relatively high-scoring countries such as Vietnam and Malaysia.

Conversely, if we return to the YouGov poll data, South American food scores relatively low in popularity. It’s no coincidence, given they produce and consume so little eggplant. Look at the production data by region.

So, there you have it. The more eggplants a country produces, the more popular their food is likely to be. Or, countries that use more eggplant have better food.

East to West along the Eggplant Road

Who needs silk when you have eggplants?

Reading Marco Polo’s The Travels, you might be disappointed to find not a gripping narrative of exploration and discovery, but rather alternating trading notes – Lanzhou: paper, three lire per sheaf; jade, eighteen lire per carob – and fantastical claims still debated by modern historians. But what if Marco Polo had done the sensible thing, and pivoted into eggplants? While he might not have made it to the court of Kublai Khan, he would have had a delicious trip through eggplant heartland. Perhaps the contours of history would have been changed, with new nations founded upon charred eggplant, wars fought over the origins of dishes and an eventual eggplant-based blockchain currency. 6

In that spirit, from France to Japan, I’ve written up some of the best eggplant recipes I could find.

the Tong Yue 僮约 by Wang Bao 王褒. ↩

Although, that same fifth-century Chinese text mentions ladies of the court using the skin to dye their teeth – so it seems like purple-skinned eggplant already existed in China and probably beyond when the white egg version arrived in Europe. ↩

A cultivar is a version of a plant selected by people for favourable attributes such as texture, taste or colour. ↩

“[they would] eat the Fruit of them boil’d with fat Flesh, putting thereto some scrap’d Cheese, which they preserve in Vinegar, Honey, or salt Pickle, all Winter, to provoke a venereal Appetite” ↩

In 2018, 619,000 tons were exported out of 54,000,000 tons grown. ↩

It turns out this already exists. We are truly living in the strangest timeline. ↩